Kūkai

The known life of Kūkai

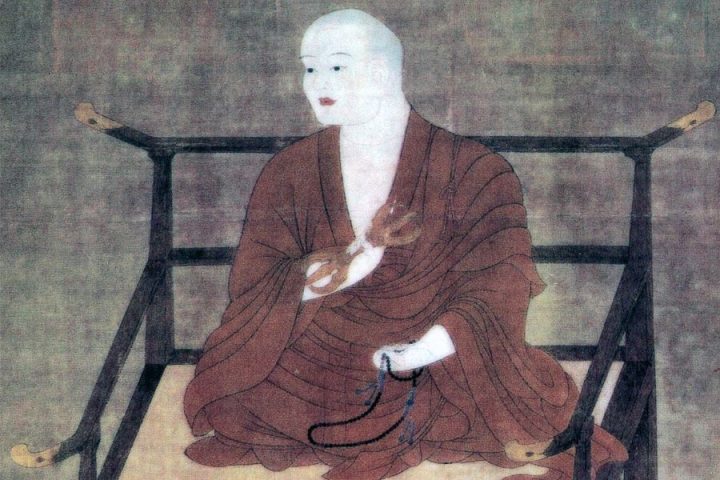

Kūkai was a Buddhist monk, born in Shikoku, who founded the Shingon or True Word sect of Buddhism. Posthumously, he has been known as Kōbō Daishi, The Grand Master Who Propagated the Buddhist Teaching. He’s referred to by Shingon followers with the honorific title Odaishisama and also by the religious name Henjō-Kongō. Besides being a monk, Kūkai was also civil servant, scholar, poet, artist and engineer.

Kūkai was born in 774 in the grounds of what is today Temple No. 75 Zentsū-ji, in the province then known as Sanuki. His family belonged to the aristocratic Saeki family, part of the ancient Ōtomo clan. He was named Mao (True Fish). The period of his youth was marked by political changes that resulted in the decline of his family’s fortunes. In 791, Mao went to Nara, then the capital of Japan, to study Confucianism at the government university.

At university, Mao became interested in Buddhism. He began chanting the mantra of Kokūzō Bosatsu, frequently visiting remote places to chant and practice ascetism. At the age of 24 he published his first major literary work, Sangō Shiiki. After university, Mao returned to Shikoku to practice a severe, ascetic form of Buddhism in the mountains. The scenes of his efforts include Mt. Ishizuchi in Ehime and a large rock at Temple No. 21 Tairyū-ji in Tokushima. While meditating on the Fudoiwa Rock on the Muroto Peninsula in Kochi, Mao attained enlightenment at the age of 30. To mark the transformation, he changed his name to Kūkai, meaning “sky and sea”, reflecting the stark view that faced him on the peninsula.

During his personal Buddhist practice, Kūkai was told in a dream that the knowledge he sought could be found in the Mahavairocana Tantra which had recently become available in Japan. But most of it was still in Sanskrit, and the portion of it in Japanese was incomprehensible, so Kūkai resolved to go to China to study the text there.

Fortunately for him, in 804 the government sponsored a mission to China for study of this tantra, and Kūkai was part of the expedition. A storm wrecked one of the four ships, and forced another to return to Japan. The remaining two ships were impounded in Fujian Province. Kūkai wrote to the governor explaining their mission, whereupon they were released and allowed to go to Chang’an (today’s Xi’an), the capital of the Tang dynasty.

Kūkai began his studies of Chinese Buddhism and Sanskrit at Xi Ming Temple, and in 805, he met the elderly Master Huiguo (746 to 805) who had eagerly anticipated the arrival of Kūkai since he had received word of his mission. Huiguo was the latest in an illustrious line of Buddhist sages, known for translating Sanskrit texts into Chinese. Having no disciples of his own to continue his lineage, Huiguo initiated Kūkai into the esoteric Buddhism tradition at the Qinglong Monastery. An education that normally took 20 years was compressed into a few months, which Huiguo described as like pouring water from one jar into another. Huiguo died soon afterwards and Kūkai returned to Japan to spread the esoteric teachings there.

Despite his new status as eighth Patriarch of Esoteric Buddhism, his mastery of Sanskrit, Chinese calligraphy and poetry, and his extensive library of esoteric texts, Kūkai faced obscurity after his return in 806. It was only in 809 that the Japanese Imperial court began to take an interest in him.

For the next 14 years, Kūkai was based at Takaosan (later Jingo-ji) Temple in the outskirts of Kyōto. Here he was supported by the new Emperor Saga, with whom Kūkai exchanged poems and gifts. In 810 Kūkai was appointed administrative head of Tōdai-ji, the main temple in Nara, and head of the Office of Priestly Affairs, marking the start of his rise to the highest levels of Japan’s religious establishment.

In 816, Emperor Saga accepted Kūkai’s request to establish a mountain retreat at Mt Kōya. The site was consecrated in 819, and work began to transform the top of the mountain as a representation of the Mandala of the Two Realms that form the basis of Shingon Buddhism. In 821 Kūkai was back in Shikoku, overseeing the restoration of Mannō Reservoir in Kagawa, which is still the largest irrigation reservoir in Japan. Today there are many stories from around Shikoku of Kūkai miraculously creating springs and wells by striking his staff on the ground, and so we can assume that the job at Mannō wasn’t his only civil engineering project. Kūkai is typically depicted as a very robust man, and his ascetic training would have put additional muscle on his physically solid frame.

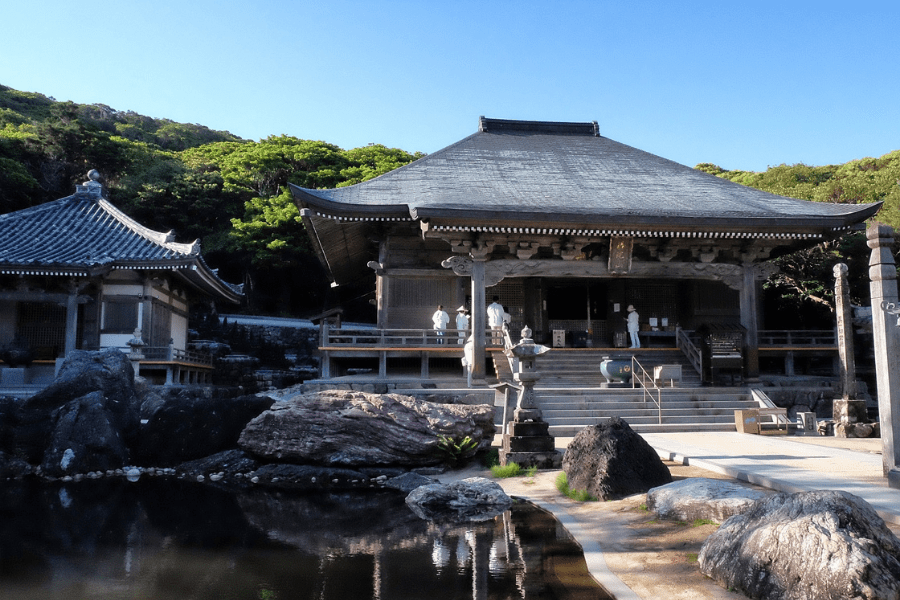

Back in Kyōto, in 823 Emperor Saga asked Kūkai to complete the construction of Tō-ji, which became the first esoteric Buddhist centre in Kyōto. Saga was succeeded by the Emperor Junna (823-833) who also favoured Kūkai, recognizing his form of Buddhism with the new name Shingon-shu, and permitting Kūkai to make exclusive use of Tō-ji for the Shingon sect.

More temple-building projects followed, and in 825, Kūkai became tutor to the crown prince. Then in 827, he was appointed to the position of Daisōzu, responsible for conducting state rituals involving the emperor and imperial family. In 828, Kūkai opened his School of Arts and Sciences (Shugei shuchi-in), a private institution teaching Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism to pupils of all social standing.

After completing a major work, The Treatise on The Ten Stages of the Development of Mind in 830, Kūkai became ill in 831. He left around fifty works on esoteric Shingon doctrine. He’s also said to have developed the combined kanji and kana writing system used today. At the end of 832, Kūkai returned to Mt. Kōya. In 835, the emperor granted permission for Shingon monks to be ordained by government license at Kōya, cementing the position of the Shingon sect as part of the state. Today, the six branches of Shingon in Japan claim more than 10,000 temples.

Towards the end, Kūkai stopped eating and drinking, and devoted himself to meditation. At midnight on the 21st day of the third month (835) he died at the age of 62. In place of the traditional cremation, Kūkai was entombed on the eastern peak of Mt. Kōya as he had wished. His body is said to be perfectly preserved and believers say that he’s still meditating, awaiting the appearance of Miroku, the future Buddha. Less than a century after his death, the Emperor Daigo bestowed on Kūkai the posthumous title Kōbō Daishi. It’s become a tradition to visit Mt. Kōya before and after undertaking the Shikoku pilgrimage.

Kūkai and the Shikoku Pilgrimage

So, did Kūkai really establish the Shikoku Pilgrimage? Although the outline of Kūkai’s life is known, the details are obscure. His whereabouts during the intervals between the specific incidents mentioned above aren’t clear.

During his visits to Shikoku for ascetic practice or engineering projects, Kūkai is popularly said to have established or visited a lot of temples and to have carved many of their images. However, Kūkai is known for certain to have visited only three temples since he mentioned them specifically in his writings; Zentsū-ji where he was born, Tairyū-ji and Hotsumisaki-ji.

Modern scholarship indicates that there was no fixed pilgrimage route around Shikoku when Kūkai lived. Before his time, national temples (Kokubun-ji) were established and visited by pilgrims. Kūkai himself established two or possibly more temples. After his time, temples were built at significant sites from his personal history. These gradually coalesced into the pilgrimage.

Other aspects of the pilgrimage such as the legends and cult of Kōbō Daishi, including the story of Emon Saburō, were developed by the monks of Mt. Kōya who travelled to promote Shingon, visiting Shikoku as well.

The tradition of the temple stamps probably arose from the restrictions on travel in the Edo period, when the movement of ordinary people was tightly regulated by a system of guard posts on major roads. Pilgrims had to obtain travel permits, follow the main paths, and pass through the guard posts within a certain time limit. The book of temple stamps represented proof of passage and a passport of sorts.

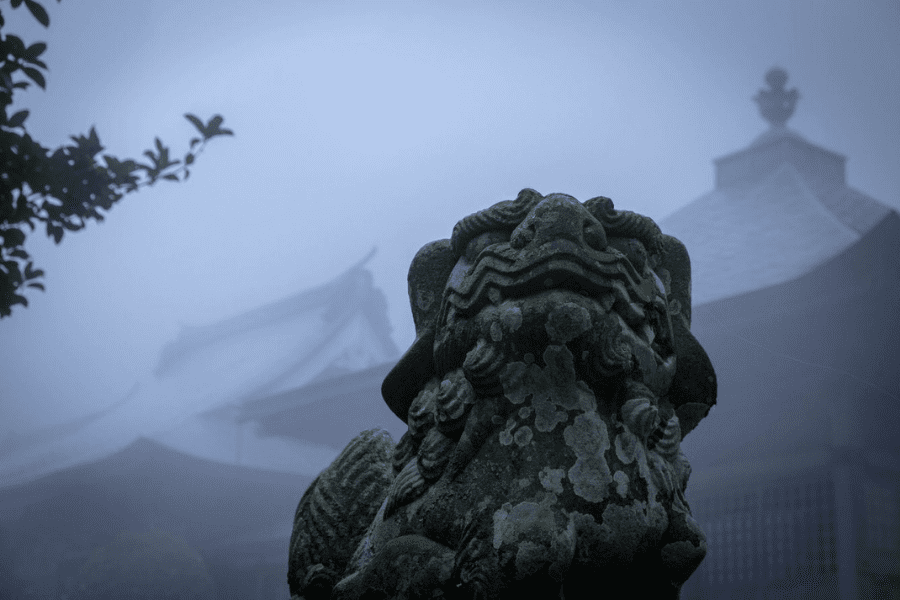

In this way, the hardware and the software of the pilgrimage developed gradually over time to become one of the great pilgrimage routes of the world. However little Kūkai may have had to do with establishing it in fact, many pilgrims, especially those who walk, experience the feeling of Kōbō Daishi’s presence, walking beside them.

Related Tours

Experience the most beautiful and interesting temples of the Shikoku Pilgrimage in seven days.

A tour for families or friends, staying in the most characterful kominka and ryokan of Shikoku.

Visit the most beautiful and interesting temples of the Shikoku Pilgrimage and walk the toughest trails.